There is a plethora of columns that get published almost daily in the local press on the parlous state of Pakistan’s economy. A common refrain of readers is that these articles are long on analysis but short on solutions. The blame for this does not rest with the generally distinguished analysts who write these pieces.

The problem is that the nature of Pakistan’s economic woes is near intractable. And it is indeed difficult to come up with ways to extricate the country from the abyss in which it now resides.

This is, as the saying goes, a tough nut to crack. However tough does not mean impossible. There is a way out. But it will take courage, resolve, intelligence and commitment to stay the course on the part of those who really decide Pakistan’s destiny.

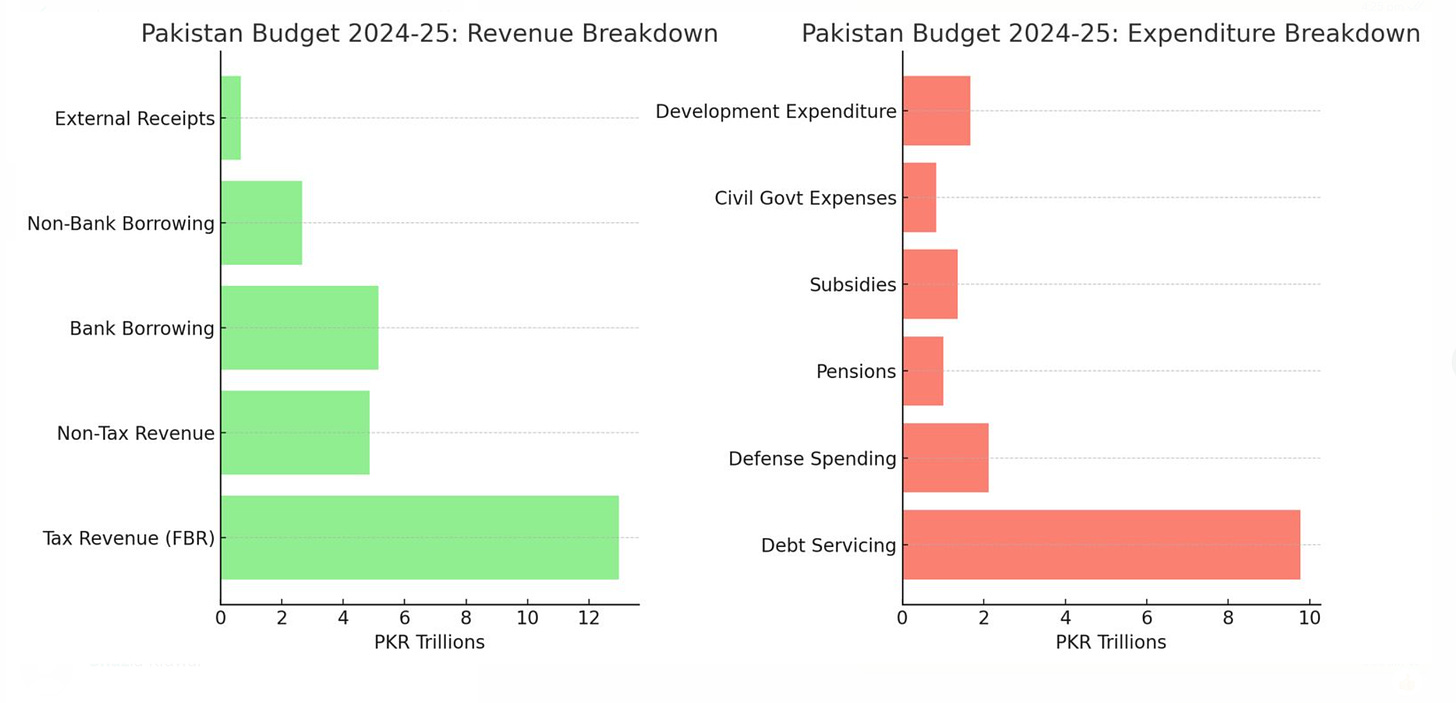

Let’s start by looking at the nature of the challenge. The two bar charts on this page tell it all. The green bars show the sources of the government’s revenue. And the orange bars show the breakdown of expenditure. The total revenue from all sources amounts to Rs 17.8 trillion. And the total expenditure to Rs.18.9 trillion. So already the government is planning to spend more than it will take in. This is irresponsible. But it is still not the main problem.

That Gordian Knot rests in the bottom bars of the two charts. The ones which show FBR collected tax revenue and debt servicing respectively. Notice that direct tax revenue amounts to Rs 13 trillion and debt servicing to Rs 9.8 trillion. So already 75% of tax revenue is taken up for servicing debt. Now consider that the budget envisions new debt to include bank and non-bank borrowing totaling Rs 7.8 trillion.

The implications are clear: One, that most of the government’s tax revenue will be used to service debt. Two, that most other government obligations will be paid out of new debt. And finally, three, the new debt of Rs 7.3 trillion will mean that debt servicing costs will be even higher in the next fiscal year.

Understand also that as of 2024 Pakistan’s total debt is approximately $ 288 billion. Of this $127 billion is owed to foreign creditors. In other words, Pakistan’s foreign debt amounts to 55-56% of its total debt portfolio. The remaining 44-45% includes loans from domestic banks, government bonds and treasury bills.

The cost of servicing our foreign debt - both principal repayment and interest - this fiscal year (2024 – 2025) is expected to be $ 28.4 billion. Bear in mind that the remittances from Pakistani workers abroad to the home country during 2024 are expected to be $ 28 billion. This is an almost exact match with our debt service payments to foreign lenders!

There is no doubt that the spiraling cost of debt will sooner or later crowd out all other costs. In the end Pakistan will exist only to service its creditors. Whatever crumbs remain will be thrown to the 250 million hapless citizens of our land who are already mired in poverty and misery.

It cannot escape the people who make the decisions on Pakistan’s future that this is not a sustainable situation. And that if we continue on this path the outcome will be a slow, painful and inevitable death.

However, all hope is not lost. There still exists a path to salvation. But it is difficult and not for the weak hearted. And those who choose to walk it must steel themselves for the harsh challenges they will face.

That path begins with the imposition of a moratorium on all foreign debt servicing – both principal repayment and interest. This will immediately free up $ 28 billion, or approximately Rs 8 trillion, for deployment in other critical sectors such as education, health care, and public services.

To be clear, the moratorium does not mean that Pakistan is repudiating its foreign debt obligations. Rather it will be a temporary measure which will give us the fiscal space to start to put the economy on a sound footing. And to negotiate possible debt write-offs and other concessions from lenders.

It must be accompanied by a host of extreme measures to restructure the economy. An axe needs to be taken to costs. All unnecessary imports should be banned including vehicles and knocked down kits, luxury and consumer goods and all nonessential food items. Shut down or sell off all loss making SOEs. Guarantee the independence of the boards of directors of all SOEs which are profitable. Remove all government employees from SOE boards and free these boards of control by ministries or their bureaucrats.

Cost cutting must be matched by revenue enhancement. If existing structures such as FBR are beyond repair. They should be replaced with a new professional tax collection organization. Use of new technologies should be optimized to enable a paperless system immune to corruption, misuse and tax evasion. Focus on not only enhancing the volume of exports but also on increasing the value added of these exports. Export of IT services must be aggressively encouraged and supported. Consider the amazing fact that our neighbour India earns more from its IT exports than Saudi Arabia earns from oil in any given year. These are just some examples of the sort of measures that need to be taken.

The moratorium on debt service will be viewed by international lenders as a default. There is no doubt that this will have serious and damaging consequences for Pakistan. These are some of the consequences:

· Access to financial markets: Pakistan will be locked out of access to international financial markets. This may not be such a bad thing since it is easy access to foreign credit that has got us into this hole to start with.

· Lawsuits: International creditors may sue the government in international courts or arbitration tribunals to recover debts.

· Asset seizures: In extreme cases, creditors might seize Pakistan’s overseas assets, such as foreign bank accounts or state-owned properties, or aircraft or ships to recoup their losses.

· Diplomatic strain: A default will strain diplomatic relations with creditor countries.

· Trade sanctions: In some cases, creditor countries may impose sanctions or other punitive measures.

In addition to these consequences, one should also expect a short-term economic decline, a rise in unemployment and possible political and social unrest.

In light of these rather serious and possibly dangerous consequences, one wonders: Is a moratorium on foreign debt a path worth walking? This is a good question. The answer hinges on the following dilemma: Avoid the moratorium and spiral slowly but inexorably into the debt trap of near certain oblivion. Or impose the moratorium, enter a tunnel of uncertainly and turmoil with the possibility of emerging at the other end as a viable, stable and successful entity. Is this a chance worth taking?